By Paul Gessell

By Paul Gessell

National Gallery’s Katerina Atanassova is putting Canadian art on the international map

The dreamy paintings of French icons Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir immediately come to mind when most of the world, including Canada, thinks of Impressionist artists. Canada, too, had Impressionist painters dating back to the late 1800s but their names, even in this country, do not trip off the tongue. And certainly, those Canadian painters are known even less in other parts of the world.

But that is changing, thanks to Katerina Atanassova, the effervescent, flamenco-dancing, poetry-writing chief curator of Canadian art at the National Gallery of Canada. Since coming to the National Gallery in late 2014, Katerina has been on a mission to place historical Canadian art in a global context.

“That is my mantra,” she says. In other words, Katerina wants to put Canadian art on the international map. Look out Monet and Renoir: The Canadians are coming.

Katerina bursts into a room for an interview like a force of nature. Her arms and hands are constantly in motion. She talks at breakneck speed. Her silver jewellery sparkles. She has come prepared, sifting through a stack of file cards, email printouts, magazines and other papers to produce documents that prove her points. She quickly inhales all the oxygen in the room. There is little opportunity for questions, only answers.

On this day, Katerina is discussing the travelling exhibition, Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880-1930, that opened amid great fanfare last summer in Munich, Germany, attracting 108,000 visitors to the Kunsthalle. That’s almost twice as many as the attendance at an exhibition the previous summer of French masters at the same venue. (Eat your heart out, France.) Katerina held a news conference in Munich at the opening of the show. More than 60 journalists attended. A Belgian reporter said she had scoured the collections of libraries containing material on international Impressionism and found not one reference to Canadian Impressionism. “That brought tears to my eyes,” Katerina recalls. “I thought if that is the case for you guys in Europe then mission accomplished for us because this is what we wanted to do. We wanted to open a new chapter. We wanted to start that visitors to the Kunsthalle. That’s almost twice as many as the attendance at an exhibition the previous summer of French masters at the same venue. (Eat your heart out, France.)

Katerina held a news conference in Munich at the opening of the show. More than 60 journalists attended. A Belgian reporter said she had scoured the collections of libraries containing material on international Impressionism and found not one reference to Canadian Impressionism. “That brought tears to my eyes,” Katerina recalls. “I thought if that is the case for you guys in Europe then mission accomplished for us because this is what we wanted to do. We wanted to open a new chapter. We wanted to start that conversation.”

Katerina held a news conference in Munich at the opening of the show. More than 60 journalists attended. A Belgian reporter said she had scoured the collections of libraries containing material on international Impressionism and found not one reference to Canadian Impressionism. “That brought tears to my eyes,” Katerina recalls. “I thought if that is the case for you guys in Europe then mission accomplished for us because this is what we wanted to do. We wanted to open a new chapter. We wanted to start that conversation.”

That feeling of “mission accomplished” accelerated as the exhibition reviews surfaced. “A sensual journey of discovery,” reported TZ, a Munich newspaper. Another German publication Kunst + Film (Art and Film) called the Canadian paintings at the Kunsthalle “a magnificent selection.” From New York to Japan, the raves accumulated, prompting the international art world suddenly to take notice. In the past year alone, Katerina has been invited to deliver presentations on Canadian Impressionism at three prestigious academic conferences in the United States. Following the triumph in Munich, the Canadian exhibition travels this year to Lausanne, Switzerland and Montpellier, France before landing, like a returning army of victorious soldiers, at the National Gallery in Ottawa. The tentative Ottawa dates are Oct. 30, 2020 until March 21, 2021.

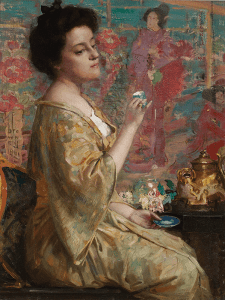

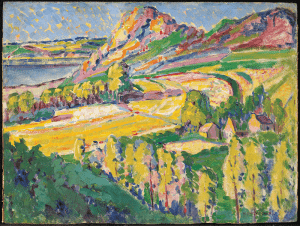

The exhibition, for the European stops, includes more than 100 paintings by the likes of Maurice Cullen (“Canada’s Monet,” says Katerina), James Morrice, Helen McNicholl and Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté. There are also works by such Canadian superstars as Emily Carr and most of the Group of Seven, who all dabbled in Impressionism early in their careers before moving onto their more familiar modernist styles.

The paintings include many snow-covered fields, scenes in upper class Victorian drawing rooms, farmers’ houses, seaside visits and well-behaved children. While these paintings were largely inspired by French works seen by Canadian artists while studying and working in France during the late 1800s, the Canadian paintings have their own style, largely because the light in Canada is “harsher” than in France, says Katerina. The Canadian scenes also seem more prim than the more festive bourgeoisie gatherings popularized by the likes of Renoir.

The exhibition will be bigger in Ottawa than in Europe with more paintings and the addition of many works on paper (pastels, watercolours and etchings) and photographs. Some paintings were deemed too fragile to travel to Europe, and then there is Frances Jones’s 1883 painting, In the Conservatory, showing a woman sitting in a Halifax room filled with exotic plants. The painting is owned by the Nova Scotia Archives and is forbidden by the province to leave the country. But it will come to Ottawa, allowing people to view the artwork crowned by this exhibition as the first true Impressionist painting done by a Canadian. Previously, that title had gone to Hamilton artist William Blair Bruce. Katerina is not afraid to rewrite history, constantly relying, she says, only upon “primary sources” rather than “secondary sources.” This is one curator who has to see the proof for herself and does not depend upon the research and opinions of others.

Other beauties in the exhibition include Lauren Harris’s, A Load of Fence Posts, 1911, showing a horse-drawn wagon framed by a spectacular winter sunrise; Franklin Brownell’s Tea Time, 1901, a portrait-like painting of a society woman, ever so properly drinking tea; and James Wilson Maurice’s Venice at the Golden Hour, 1901-2, depicting the Italian city breathtakingly aglow.

Katerina immigrated from Bulgaria as a young woman with a degree in medieval art. Shortly after arriving in Canada, she fell in love with the Group of Seven and Canadian art in general. The Group “spoke to me on a different level from what I was used to seeing in European museums,” she says. “They had that sense of freshness and uniqueness that were making them stand out from experiences I had had before. Maybe as a newcomer, I was looking for this unified language to describe the new land I was coming to.”

She quickly ascended the corporate ladder at various galleries, becoming chief curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection at Kleinburg, near Toronto. That institution is the holy of holies for the Group of Seven. But it was a sacred spot headed for a shake-up with the arrival of Katerina. The art world was aghast at the news she planned to exhibit Toronto artist Kim Dorland, who has been labeled “Tom Thomson on acid,” right beside the century-old works of Thomson, the man sometimes called “Canada’s Van Gogh.” Surely, Thomson would roll over in his grave. But the exhibition was a success, the critics had to admit. Another shock came with the news she was planning a show of Canadian art all about Marilyn Monroe. That was another success that broke attendance records at the McMichael. But the greatest victory came with the exhibition Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. That’s the exhibition Katerina took to Europe, setting attendance records in England, Norway and The Netherlands. It was not the first trip across the Atlantic for those artists but it was their most triumphant in a century.

It was during Katerina’s time at the McMichael that she started dreaming of a major Canadian Impressionist show. That became a possibility after she joined the National Gallery. But first she had another big task: to rehang the entire permanent Canadian collection at the gallery, incorporating Indigenous art alongside mainstream art of the same time periods. She also vastly increased the representation of female Canadian artists in the gallery. It’s still only one-third women, but that is far more than ever before.

Katerina is hoping to build upon her success last year in Germany with another Canadian show she is curating along with the Art Gallery of Ontario, this time in Frankfurt, to run from Sept. 25, 2020 to Jan. 10, 2021. The exhibition, Magnetic North, will showcase 80 paintings and 40 sketches, mainly from the Group of Seven. Plus, she is plugging away at an exhibition she has wanted to do for years, showcasing “urban art” from pre-Confederation to the present. Dates for that have yet to be set. There are never enough hours in the day to devote to all her projects.

Shortly after arriving in Ottawa more than five years ago, Katerina happily reported that she had found a studio in the city where she could practice her beloved flamenco dancing. Surely she is a natural, being so flamboyant, stylish and dramatic. But now she says she no longer has time to practice.

“I’m burning the midnight oil, always,” she says. That’s not a complaint, by the way, the absence of flamenco notwithstanding. You can tell she loves every minute of her work.