By Paul Gessell

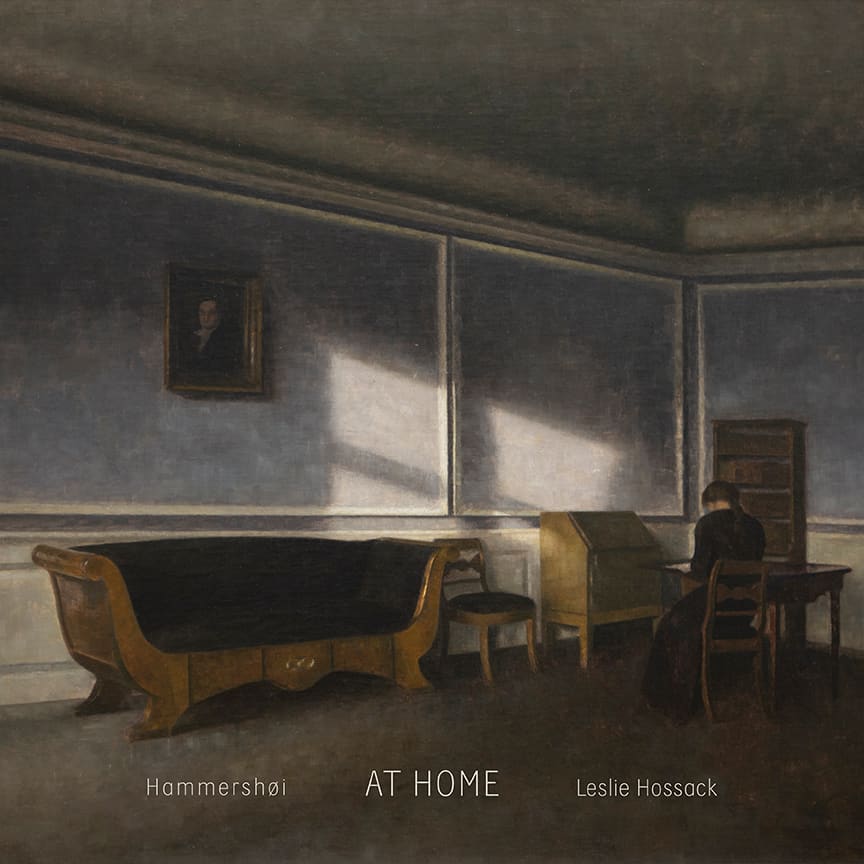

Cover photo: Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916), Sunshine in the Drawing Room (Solskin i dagligstuen), detail, 1910. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photograph by Leslie Hossack.

When Ottawa photo-artist Leslie Hossack set out to document the life of Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916), a Danish artist celebrated for his arresting interior scenes, she focused her lens on a fitting art form for our times.

Leslie Hossack was “smitten.” It was definitely love at first sight when the Ottawa photo-artist visited a 2018 exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada called Impressionist Treasures. The show featured 76 works mainly from the Ordrupgaard Museum in Copenhagen. Included were six paintings from the early 1900s by the Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi. Each canvas showed the interior of rooms in the artist’s Copenhagen apartment. The tones were muted; the furnishings sparse; visitors were drawn into a silent, introspective realm.

Hossack spent the next two years photographing everything Hammershøi. She still has at least another year to go before she will complete an art project about this artist who, in the past decade or so, more than a century after his death, has been getting the superstar treatment in Europe, Japan and elsewhere.

“Every major collection should have a picture by him,” Paul Lang, then the chief curator of the National Gallery, said in a 2018 interview with Artsfile.ca. Lang had spearheaded the gallery’s acquisition, a year earlier, of its first and only Hammershøi painting, Sunshine in the Drawing Room, from 1903. Few Hammershøi paintings hit the market these days and, when they do, the prices are increasingly higher. The gallery has also acquired a Hammershøi drawing, Group of Trees along the Royal Road near Gentofte, Denmark, 1892.

Soon after the 2018 exhibition, Hossack traveled to Denmark and France, photographing 100 of the artist’s paintings exhibited on the walls of art museums. She researched Hammershøi’s life with considerable help from the National Gallery, photographing neighbourhoods he frequented and letters he had written.

“By holding those pages, I touched his DNA,” Hossack says during an interview at her Rothwell Heights home.

During Hossack’s research, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. Hammershøi’s paintings of introspective interiors seemed like the perfect companions for the “stay-at-home, work-at-home” crisis. Suddenly, we were all forced into Hammershøi’s contained world.

In the summer of 2021, Hossasck will publish a book of her photographs called AT HOME: Hammsrshøi. Then, next fall, she is to have an exhibition of her photographs at Studio 66, a commercial art gallery in the Glebe. After that, she is hoping to have an expanded exhibition at a public gallery. (Discussions are ongoing.) For that proposed exhibition, she is collaborating with Michel Cheff, a veteran artist and curator whose resumé includes senior posts at the National Gallery, Winnipeg Art Gallery and Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

Why does Hammershøi’s work so resonate with Hossack?

“I saw my work when I looked at his work. His paintings and my photographs spoke the same visual language.”

Hammershøi’s paintings of rooms in his apartment were carefully staged. By comparing the paintings with old photographs, Hossack discovered that the artist removed most of the furniture and clutter from the rooms before painting them. Hossack’s approach is similar in her best-known photographs, those of iconic European architecture associated with such 20th century figures as Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini and Churchill. Through Photoshop, she removes the clutter surrounding the buildings. Gone are people, graffiti, parked cars and the scars of time, to reveal idealized, somewhat surreal, structures as their original architects envisaged.

Collection: Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen.

Photographed by Leslie Hossack in Impressionist Treasures: The Ordrupgaard Collection, at The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2018.

Collection: Davids Samling, Copenhagen.

Photographed by Leslie Hossack at The David Collection, Copenhagen, 2019.

Don’t be surprised if Hossack’s forthcoming exhibitions include photographs taken inside her own home, where she has been experimenting with Hammershøi-inspired staging, temporarily decluttering rooms to create a melancholy, near empty space, best lit by the autumn sun. “Poor Emmett,” Hossack says, referring to her husband and chief furniture arranger.

For Hossack, viewing Hammershøi’s interiors is an intimate experience.

“One enters his private home, moves around his physical space and then slowly encounters one’s own soul. Hammershøi projected his inner world onto his canvases and there I met him….When you fall in love with Hammershøi’s domestic surroundings and psychologically charged interiors, you enter your own personal labyrinth where you encounter endless open passages and countless locked doors. You confront a multitude of windows through which light passes but from which you cannot see the outside. Hammershøi’s calm, quiet, soothing, poetic interiors require you to look inward. His work is deceptively silent, somewhat subversive, and totally seductive. I was seduced.”

Leslie Hossack came to photography rather late in life. Shortly after retiring as a school principal, she took a course at the School for Photographic Arts: Ottawa. There, she bonded with three other women pursuing photography as a second career. Collectively, the foursome called themselves Studio 255, a number reflecting the total of their ages when the hobbyists turned pro in 2007. Michael Tardioli, director of the photography school, mentored the group. He called the women “disciplined” and “relentless.” The foursome traveled the world together, each with her own agenda to capture some aspect of a major European capital. Hossack initially focused on the architecture that helped define the Fascist and Communist eras. Her career took off with books of her work, exhibitions, awards and a stint as a military artist with the Canadian Forces in Kosovo. She has exhibited at such venues as the Canadian War Museum, the Military Museums in Calgary, the Diefenbunker, the National Churchill Library and Center at George Washington University in Washington D.C. and the Nikkei National Museum in Burnaby, B.C. Awards include an International Photography Award and the RBC Emerging Artist Award.

No project seems to have captured Hossack quite like Hammershøi. The artist, she says, wanted his work to be seen in a gallery. So, Hossack is replicating the gallery experience by photographing the

Collection: Davids Samling, Copenhagen.

Photographed by Leslie Hossack at The David Collection, Copenhagen, 2019.

paintings in their frames on gallery walls. Hossack’s photographs will be seen just as gallery visitors see the original paintings even though that means the lighting is not always perfect and slight distortions or reflections can be seen on the glass fronting some of the paintings. The one change Hossack has made is to place the photograph of each canvas and frame on a black background, to provide a unified look to the works.

“I fell in love with his work seeing it in an exhibition in a gallery,” says Hossack. “So, that’s the way I want to show it.”