By Paul Gessell

Photographer Christine Fitzgerald wants you to shudder when viewing her beautiful, though-provoking works. That’s easy.

Christine Fitzgerald’s self-described “obsession” began in 2012. She had just retired as executive vice-president of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, a federal government agency. That year, Christine’s husband gave her a camera for Christmas, “which he probably regrets now.” It was not a fancy camera, just an “entry-level” Canon. That camera totally changed her life.

“I became obsessed,” the chatty, high-energy photographic artist confesses during an interview in her spacious Ottawa South studio. “I had to know everything about that camera. I wore that camera out. I think I took photos every day—and I’m not exaggerating—every day for two years solid. I had to perfect everything, like birds taking off in flight. I would spend five hours on the Ottawa River, just doing it over and over until I had a perfect bird.”

A definite perfectionist, Christine started buying more sophisticated cameras and lenses. Within a few months she had taught herself as much as she figured was possible. So, she turned to the experts for guidance and enrolled in the two-year diploma program at the highly rated School of the Photographic Arts: Ottawa.

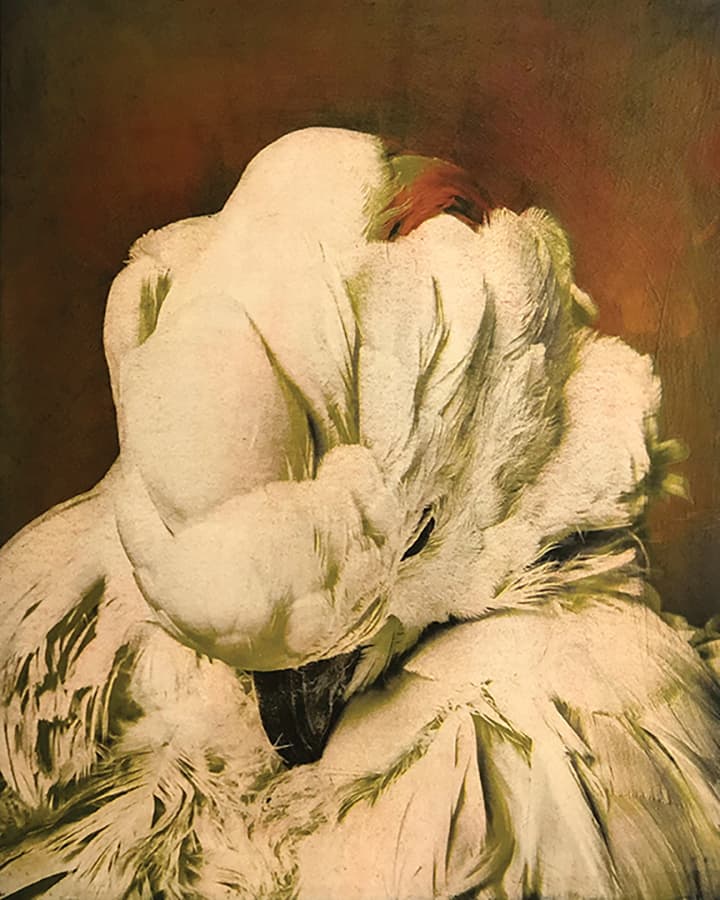

Tricolour gum bichromate over palladium print.

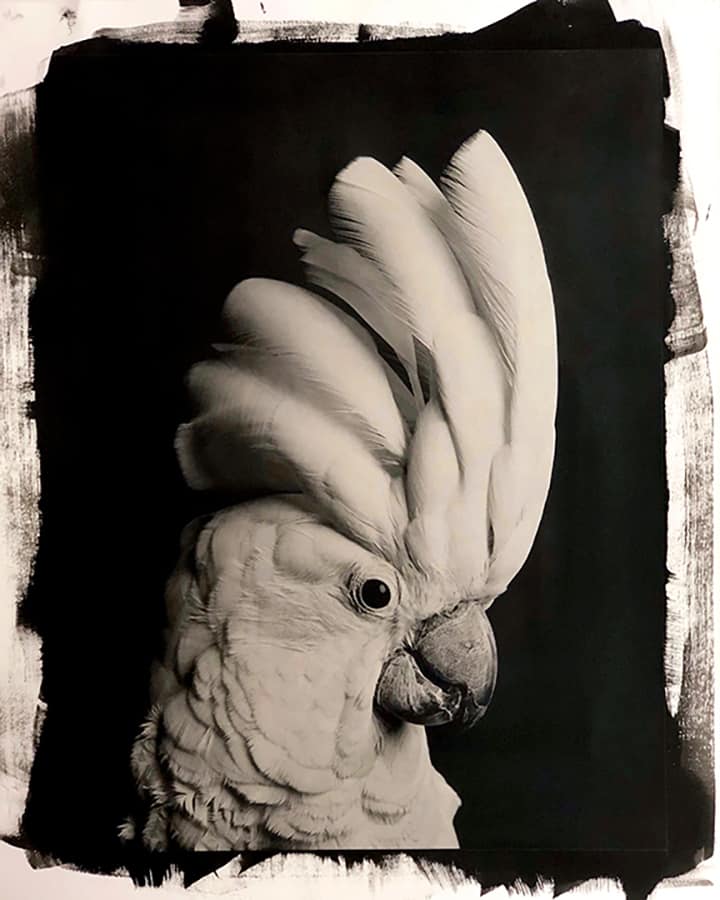

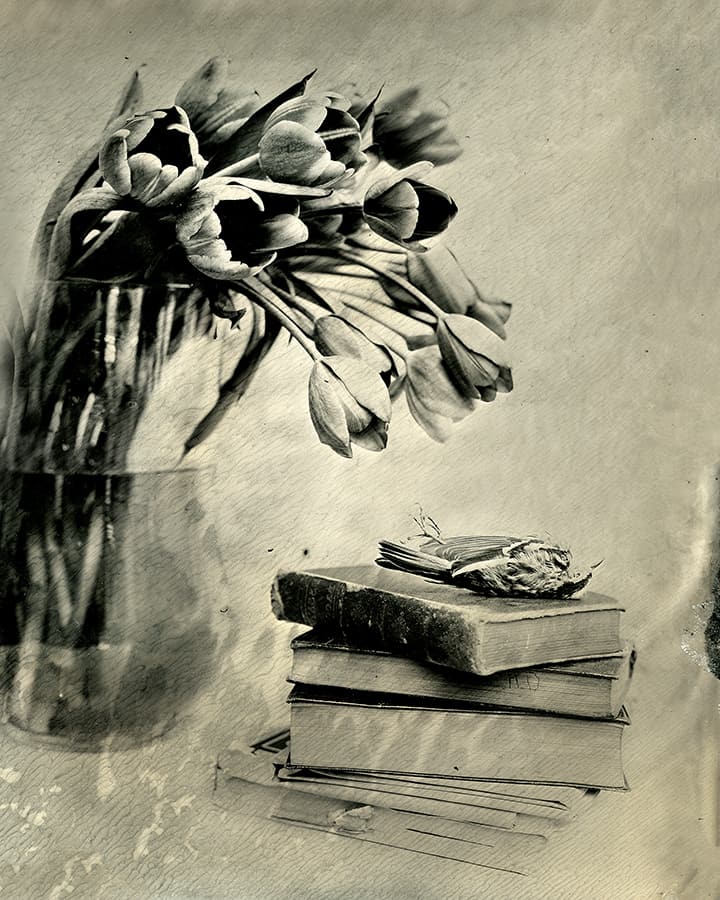

At SPAO, Christine discovered the 19th century wet-collodion plate photography process, a time-consuming, complicated endeavour that involves skill, patience, long exposures, chemicals and the necessity for a portable darkroom. It’s a process that makes the resulting photograph look antique. Imperfections in the final print are not just visible, but desired. A photograph of a bird or pear or person evolves from the strictly representational to an aesthetically astonishing work of art, the difference as profound as between an ordinary photograph and an Impressionist painting.

“I love the tonality,” Christine says of the wet-collodion process. “I love the imperfection. I learned from this process how to embrace imperfection.”

Some of these “imperfect” photographs, including individual portraits of three generations of women in one Mohawk family, are part of the seven-month, multi-artist exhibition Open Channels that runs until January 26 at Ajagemo, the Elgin Street gallery of the Canada Council for the Arts.

“I have worked with historical photography for many years, and am captivated by Christine’s interest in resurrecting obsolete processes,” says exhibition curator Melissa Rombout. “The process is tricky, prone to random imperfections and not guaranteed to produce the desired outcome.”

Christine is best known as an unorthodox, black-and-white wildlife photographer. Consider her most famous body of work, TRAFFICKED (she loves capital letters), completed last year. She was invited into a secret facility of the Wildlife Enforcement Directorate of the federal environment department housing parts of endangered animals seized at the border, either for import or export.

Some of the body parts—a zebra paw, a crocodile claw, rare turtles, ivory jewellery, a stuffed lynx—were then photographed, along with various props, to resemble still life arrangements in Old Masters paintings. Saiga antelope horns were stuck in candleholders and posed beside a wine glass and bottle; a rhinoceros horn became a fruit-filled horn of plenty; a bear’s gallbladder stood between two similarly shaped Bosc pears. The final prints are breathtakingly beautiful when first seen. And then you shudder upon realizing what exactly is being photographed. Christine wants you to shudder.

“My idea making something beautiful is to get your attention,” she says. “Then you read the narrative and you realize what you’re looking at. I do it on purpose.”

Christine’s approach is similar to that of Canadian superstar photographer Edward Burtynsky. His aesthetically pleasing images of tailing ponds, open pit mines and other environmental horrors are favourites of the National Gallery of Canada. Burtynsky is an environmentalist and uses his arty photographs to increase awareness of the planet’s degradation. But Burtynsky also has his critics, who brand his photos “pollution porn’’—titillation from pollution that does not really make people more environmentally conscious. So far, the critics have not turned on the Ottawa photo artist and her collection of body parts.

National Geographic, home of quality nature photographers, published a story and photos from TRAFFICKED. At last count, the online hits were 3.5 million. The Washington Post and some Canadian news media also ran articles and the photographs. Doors suddenly opened for Christine. The Jane Goodall Institute came calling, resulting in a portrait taken of the legendary primatologist last year on her 85th birthday. Christine demanded much before photographing Goodall in Toronto: the shoot had to be between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. to capture the best light, there had to be a portable darkroom, the room had to have a window with no nearby buildings to obscure the view, and Goodall could only wear certain colours.

The list went on. It was the kind of list certain movie stars supply when reserving a hotel room, a list perhaps demanding a bowl of Smarties, but just the red ones, on the night table.

“I thought this would never happen,” Christine says. “They gave me everything on my list.”

When celebrities like Jane Goodall comply with your red Smarties list, you know you have arrived. Michael Tardioli, founder of SPAO, is not surprised at Christine’s rocketing success. “Talk about a work ethic,” gushes Tardioli. “My God. Twelve hours a day are nothing for her.”

When SPAO opened in 2005, Tardioli expected his students would be young people starting their first career. But he was soon surprised to see people desiring a second or third career. (Christine was a nutritionist and administrator.) Another one of SPAO’s second-career success stories is Leslie Hossack, a retired Ottawa school principal whose photographs of architecture and battlefields are exhibited internationally.

Both she and Christine are represented in Ottawa by Studio Sixty Six, a Glebe gallery that is increasingly becoming the spot in the capital for unique contemporary art. “Christine’s work has everything we look for in a Studio Sixty Six artist,” says Carrie Colton, gallery director. “Her work is beautifully designed and composed; she has mastered her craft in terms of the style of photography she does, the century old wet-collodion plate process; and I truly love and believe that the messages relayed in Christine’s work are extremely important: endangered species and the erosion of planet.”

Christine’s latest exhibition at Studio Sixty Six, on show through November 24, is called CAPTIVE. (There are those capital letters again.) The photographs are of parrots, many physically and psychologically damaged by previous owners, that are now housed at Parrot Partners Canada, a rescue shelter in Carleton Place. Still using 19th century techniques, Christine has coloured the parrot photographs instead of creating her usual black-and-white images. The resulting photos look like faded paintings, often revealing the birds’ unique personalities, along with their infirmities.

“My intent with this new undertaking is to celebrate not just the natural beauty and character of parrots, but also to express through these birds who we are as humans, and how we shape our world,” Christine says in an artist’s statement. “I hope that my images will not only give voice to the parrots, but will serve to mirror us as individuals, to hold true as memento mori—reminding viewers about their own mortality and the fragility of life.”

CAPTIVE is one more way for Christine “to embrace imperfection.” In this case, that imperfection involves both style and content, the antique, imperfect look of the images and the imperfections of the damaged parrots. The history of CAPTIVE and its imperfections essentially dates back to that aforementioned 2012 Christmas present, the gift that keeps on giving to all those who are full of admiration and concern for the creatures of this planet.